To illustrate the problem of ambiguity in smart contracts, James points out to three ways that we might identify the meaning of a program. 2+2 in Python evaluates to 4 because that’s how the language was defined by humans not because there is some true Platonic form of mathematical representation. The idea that there is a technical meaning standing apart from a social meaning, he says, is just wrong. “Everything I just said is wrong,” says James. They’re precise, deterministic, and reliable. To summarize: legal contracts are run by humans who are fallible, while smart contracts are run by computers.

Finally, you can give the smart contract control over the assets. Next, by de-centralizing the decisions, miners will collectively prevent mistakes. If you write the contract as a computer program, the program is unambiguous. Smart contracts provide answers to many of these sources of uncertainty, in theory. And you can’t always get your property back because it was destroyed, or sold to a third party. Some defendants have no assets to pay, have fled the jurisdiction, or just have vanished into thin air. And not every court judgment is worth the paper it’s printed on. In this case, parties went to court over whether the definition of “chicken” meant “any bird of that genus” or vs “any young chicken suitable for broiling and frying.” You might try to define the terms more clearly, but the debate can get ever more nuanced over the meaning of “chicken.”Ĭourts also make mistakes, says James. James talks about language ambiguity through the story of Frigaliment v. Can the blockchain solve the problem of legal ambiguity? Finally, parties can escape enforcement, ignoring the terms of the contract. Second courts make mistakes and fail to enforce the contract. First, language is ambiguous: a contract’s meaning might be unclear. What are the advantages of a smart contract compared to a legal contract? Typical legal contracts have three sources of uncertainty. By embedding terms of a contract in hardware/software, smart contracts manage automated interpretation and enforcement of contracts. Smart contracts don’t have to run on a blockchain- although today’s talk will focus on the blockchain. If this works well, you reduce the need to trust the counter-parties or centralized recordkeepers. The blockchain is a transactional ledger that is cryptographically secure, does not require a centralized recordkeeper, uses incentives to ensure consensus.

James opens up by introducing blockchain ideas. When I recently asked if I could publish this post, James said that while his ideas have developed further, it’s a good summary of his thinking at that time. He helps lawyers and technologists understand each other, applying ideas from computer science to problems in law and vice versa.

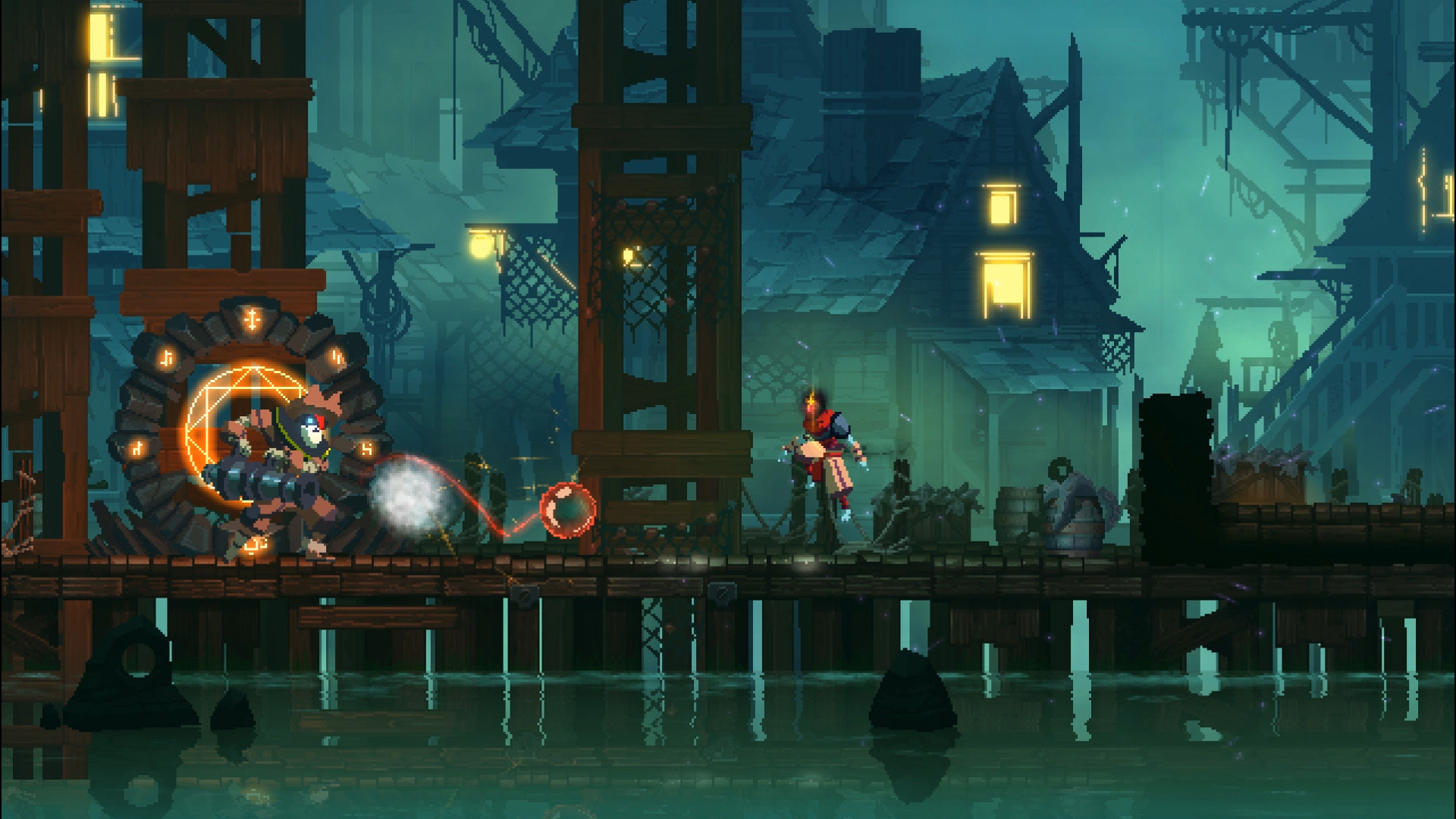

I HAVE ALTERED THE DEAL SOFTWARE

James Grimmelmann is a professor of law at Cornell Tech and Cornell Law School, where he studies how laws that regulate software affect freedom, wealth, and power. I recently found a notes from a great talk on this topic by James Grimmelman in December 2018 that I never published, from my time at the Princeton Center for Information Technology Policy. What do smart contracts provide that legal contracts don’t? How do both kinds of contracts manage problems of ambiguity, and how can blockchain systems manage ambiguity well?

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)